Phylogenetics III

Bayesian phylogenetics

Public Health Modeling Unit

2025-08-19

Barney Isaksen Potter

Series overview

Trees, tree likelihoods, and models of evolution

Rate heterogeneity and maximum likelihood

Bayesian phylogenetics, Markov chain Monte Carlo, and summary trees

Phylogeography and Kingman's coalescent

please bear with me, timing may be off

Thank you Philippe

"the global workhorse of genomic epidemiology"

One Tree to rule them all, One Tree to find them, One Tree to bring them all and in the darkness bind them

The (maximum likelihood) method we've learned so far gets a single tree

The one it finds is likely not the "best"

Are we doing a good job of reporting a single tree?

ML produces a "point estimate" or a single inference of parameters:

Tree

Branch lengths

Model parameters

Frequentist philosophy

Probabilities refer to the outcome of experiments (i.e. data)

Probabilities are objectively real in the same way that physical objects are real

"Likelihood" referes to the degree to which data support a hypothesis

Frequentist = ML

Probabilities cannot exist without data/experiments

Bayesian philosophy

BOTH data and model parameters are described by probabilities

Probability represents the degree to which we believe a hypothesis

Hypotheses can have probabilities in the absence of data

We already know things about reality

We are interested in quantifying uncertainty

Bayesian inference

First, we will discuss Bayesian inference generally

Fundamentals of Bayesian inference

Bayesian inference produces a posterior probability distribution instead of a single MLE

The posterior combines information from both data and prior knowledge

Each parameter in the model has a prior probability distribution representing known knowledge about that parameter

Combine prior knowledge with data

Create a posterior distribution

Distribuion (rather than point estimate) helps us quantify uncertainty

"Human heights follow a uniform (flat) distribution between 1 angstrom and the width of the universe."

Technically proper, but extremely uninformative prior means that the data provide all the information

"Human heights follow a uniform (flat) distribution between 1 angstrom and the width of the universe."

Technically proper, but extremely uninformative prior means that the data provide all the information

"Human heights follow a uniform (flat) distribution between 1 angstrom and the width of the universe."

Technically proper, but extremely uninformative prior means that the data provide all the information

"Human heights follow a uniform (flat) distribution between 1 angstrom and the width of the universe."

Technically proper, but extremely uninformative prior means that the data provide all the information

"Human heights follow a normal distribution with mean 170cm and standard deviation 5cm."

We can wikipedia some facts about humans

Same data as before

Now there are two distributions that we need to combine

"Human heights follow a normal distribution with mean 170cm and standard deviation 5cm."

Only two data -> posterior is similar to the prior

Lots of data -> posterior is driven by the data. Maybe we aren't sampling from all humans

How can observing data (X ) change our belief in a hypothesis ($\theta$ )?

Talk through posterior, model, prior, then marginal

How can observing data (X ) change our belief in a hypothesis

($\theta$ )?

This term is a constant, represents the probability of the data if we integrate over all possible hypotheses

How can observing data (X ) change our belief in a hypothesis

($\theta$ )?

This term is a constant, represents the probability of the data if we integrate over all possible hypotheses

How can observing data (X ) change our belief in a hypothesis

($\theta$ )?

This term is a constant, represents the probability of the data if we integrate over all possible hypotheses

How can observing data (X ) change our belief in a hypothesis

($\theta$ )?

This term is a constant, represents the probability of the data if we integrate over all possible hypotheses

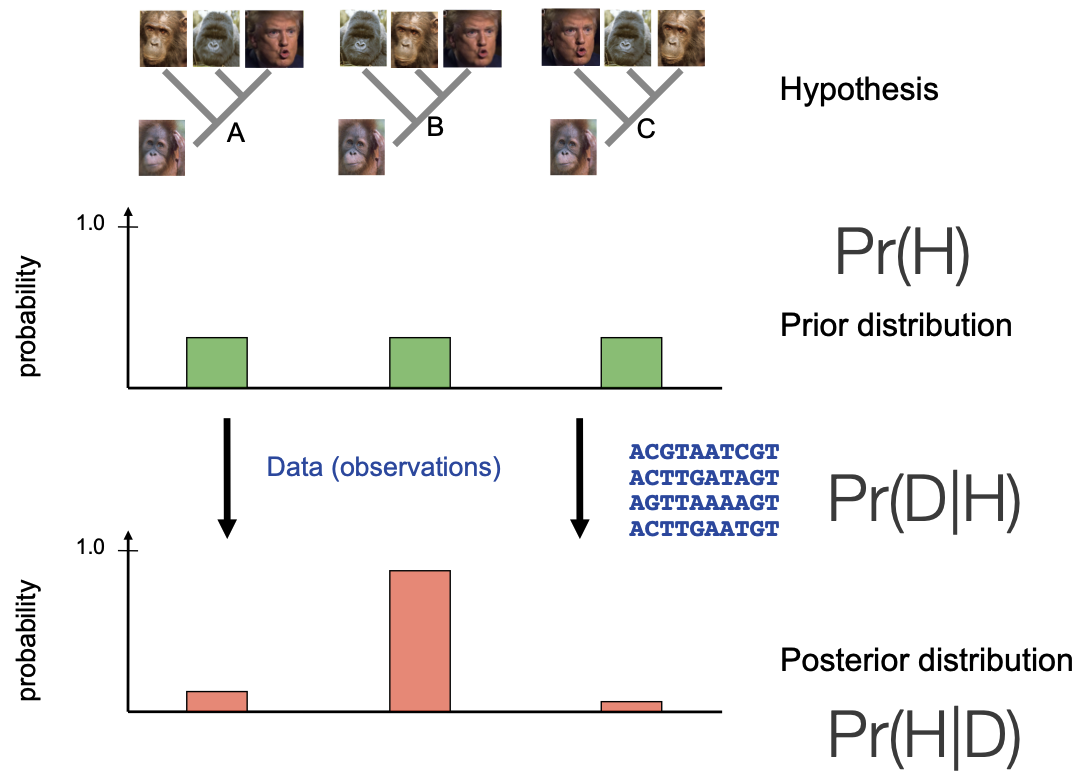

How can we apply this framework to phylogenetic inference?

We have multiple competing hypotheses for how four organisms could be related

No reason to favor one over the other -> uninformative prior

We apply data in the form of sequence data in tree likelihood calculations

We end up with aposterior distribution of trees that is informed by the data

\[

P(\theta|\textbf{X}) = \frac{P(\textbf{X} |\theta) \times P(\theta )}{P(\textbf{X})}

\]

We are now going to just change the symbols we use to fit our purpose

The posterior probability of a phylogenetic tree, $\tau$:

$\tau = $ phylogenetic hyopthesis (tree)

$\textbf{X} =$ genomic sequence data

Likelihood calculation

$\begingroup \color{darkmagenta} \tau = \text{tree topology} \endgroup, \begingroup \color{darkblue} \nu = \text{branch lengths} \endgroup, \atop \begingroup \color{mediumseagreen} \Theta = \text{model parameters} \endgroup, i \in \text{sites in genome}$

Let's break down the first term

Expand the likelihood to consist of four parts

Tree topology (shape)

Branch lengths

Model parameters

Data observations at each of the N sites in the genome

Because we assume sites are independent we can take the product of probabilities across all N sites

Calculated the same way as in ML

Prior calculation

$\begingroup \color{crimson} B(s) = \text{number of possible topologies} \endgroup$

Uniform prior on tree shapes

If we have other parameters, they will also have priors that get multiplied here

Marginal term calculation

To calculate this we need to sum the density across every possible tree...

Recall: we are calculating the average probability of the data across all possible hypotheses.

This means we are essentially performing a discrete integral over every possible tree topology.

... but tree topology space is too big!

\[\tiny

\begin{array}{cc}

\text{Num.~taxa} & \text{Num.~topologies:} \begingroup \color{crimson} B(s) \endgroup \\ \hline

1 & 1 \\

2 & 1 \\

3 & 3 \\

4 & 15 \\

5 & 105 \\

6 & 945 \\

7 & 10,395 \\

8 & 135,135 \\

9 & 2,027,025 \\

\vdots & \vdots \\

20 & 8,200,794,532,637,891,559,375 \\

\vdots & \vdots \\

769 & 3.753 \times 10^{2,110} \\

\end{array}

\]

This should be familiar already

Number of topologies scales superfactorially with number of taxa

Number is intractable for even relatively small datasets

8 sextillion: on the same order as the number of grains of sand or number of possible udoku grids

\[

3 \times 5 \times 7 \times \mathellipsis \times (2n-3)

=

\frac{(2n-3)!}{2^{n-1} \times (n-1)!}

\]

We derive this by considering, for each topology of n-1 taxa, how many places we could add a new branch along a prexisting one

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

We need a clever algorithm to perform these computations

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampling

Posterior probabilities are difficult to calculate analytically. However, we can sample values from the posterior distribution with a frequency proportional to thir posterior probability by using MCMC.

We can numerically approximate the full calculation by taking samples from the posterior distribution. If those samples are taken proportional to their posterior probability then we can summarize the samples to summarize the posterior.

Recall: ML optimization

ML uses a "hill climbing" algorithm to find the maximum likelihood, and only ever steps uphill. Downside: we don't know the shape of the distribution, and we may get caught in a local optimum

Recall: ML optimization

ML uses a "hill climbing" algorithm to find the maximum likelihood, and only ever steps uphill. Downside: we

don't know the shape of the distribution, and we may get caught in a local optimum

Recall: ML optimization

ML uses a "hill climbing" algorithm to find the maximum likelihood, and only ever steps uphill. Downside: we

don't know the shape of the distribution, and we may get caught in a local optimum

Recall: ML optimization

ML uses a "hill climbing" algorithm to find the maximum likelihood, and only ever steps uphill. Downside: we

don't know the shape of the distribution, and we may get caught in a local optimum

Recall: ML optimization

ML uses a "hill climbing" algorithm to find the maximum likelihood, and only ever steps uphill. Downside: we

don't know the shape of the distribution, and we may get caught in a local optimum

Recall: ML optimization

ML uses a "hill climbing" algorithm to find the maximum likelihood, and only ever steps uphill. Downside: we

don't know the shape of the distribution, and we may get caught in a local optimum

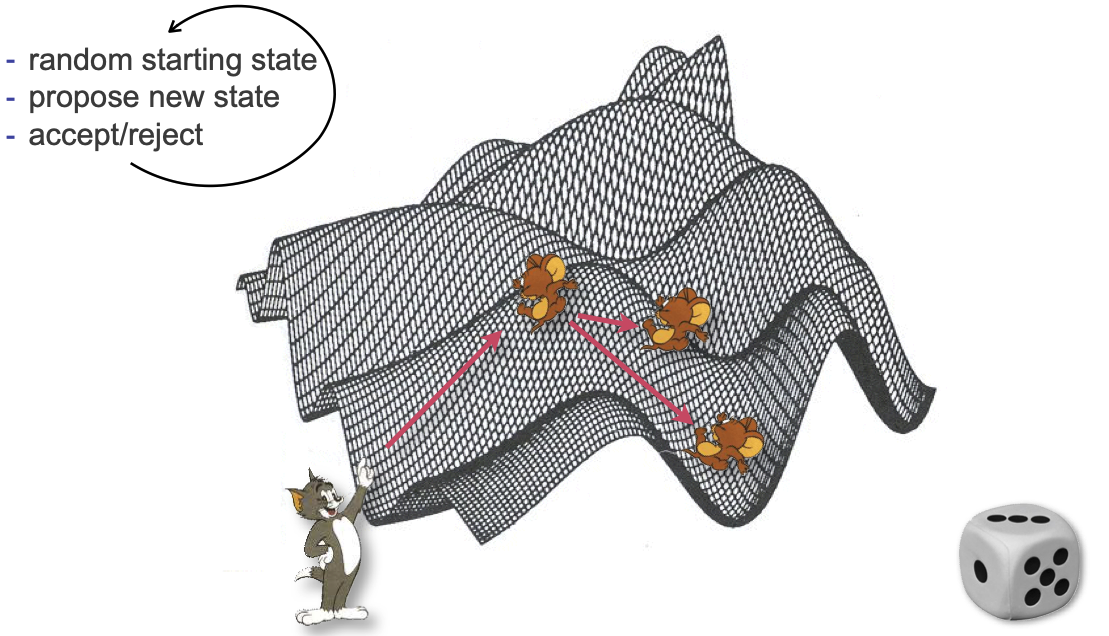

MCMC leverages randomness

Consider the black dots now

Use randomness cleverly to allow steps "downhill", in such a way that we end up with samples that cover the distribution proportional to its height

Green: we can have many steps downhill, though it is unlikely

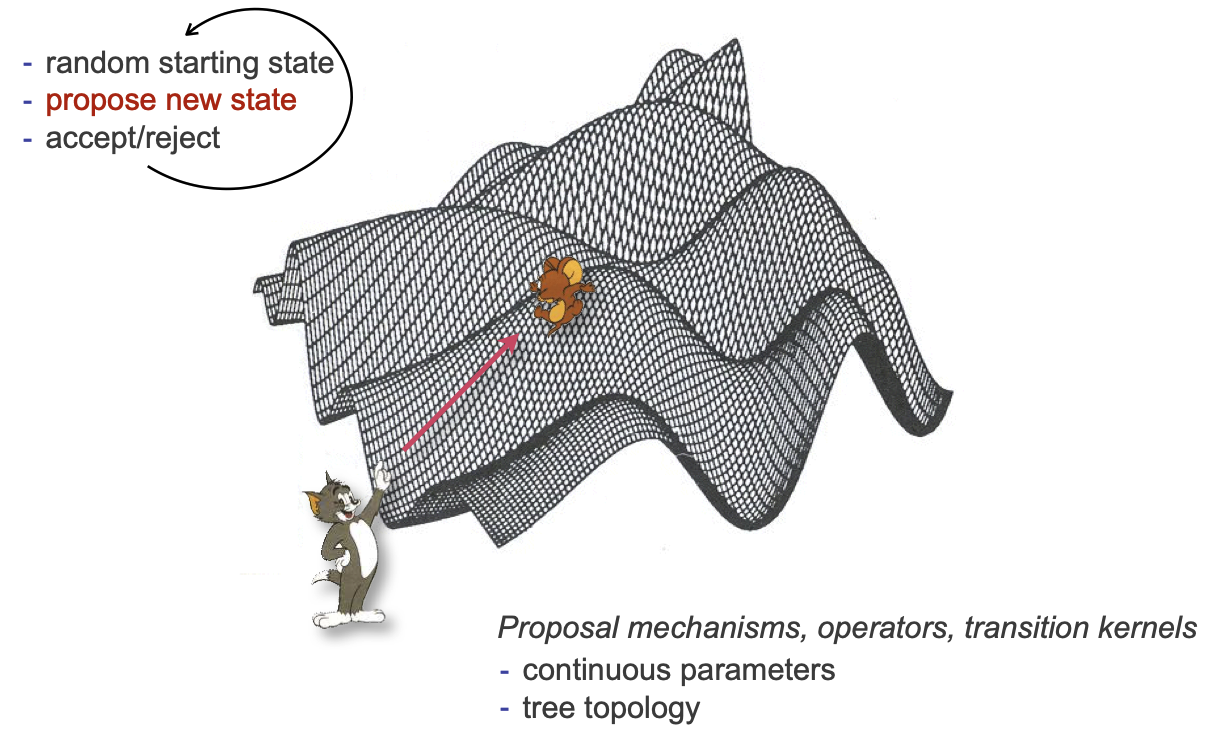

Metropolis-hastings algorithm

Core idea of the MH algorithm:

Start with a random state (calculate its likelihood)

Propose a random step from that state

Based on the likelihood at the new state, either accept or reject

Repeat (a lot)

Recall: our state tau=tree, nu=branch lengths, Theta=model parameters

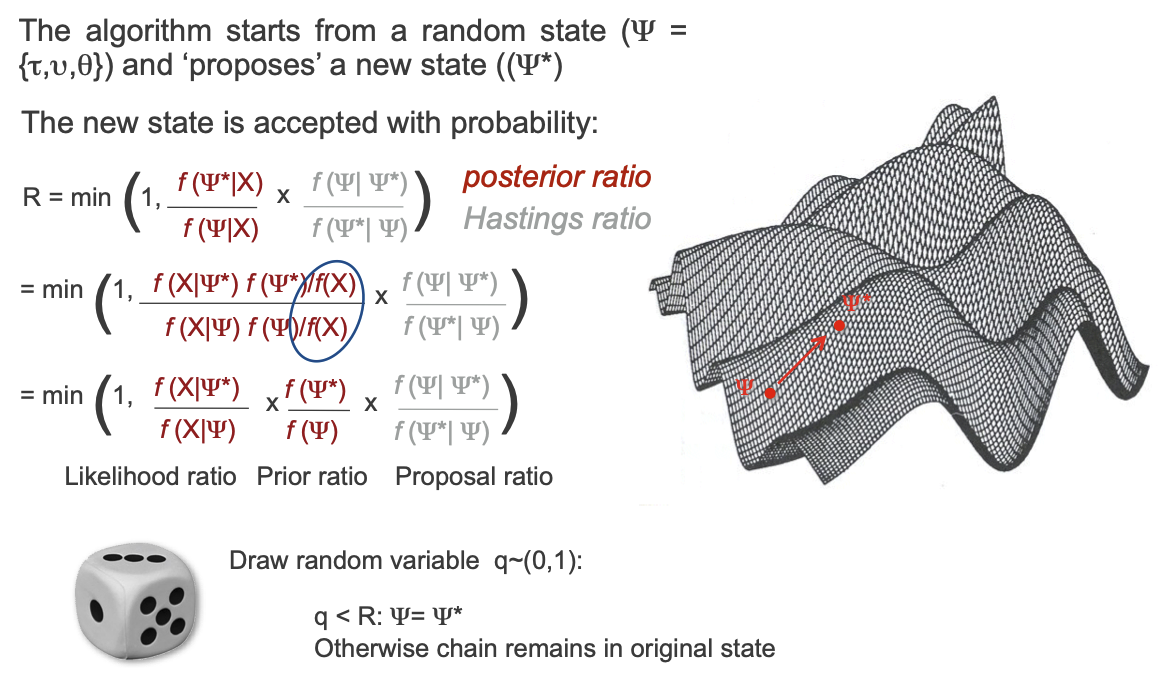

The algorithm proposes a new, modified state Psi star

Calculate a ratio R:

Ratio of posterior probabilities

Term "Hastings ratio" that accounts for potential asymmetry in proposals (ignore)

Expand posterior probabilities according to Bayes' theorem

Same problem as earlier, except that the marginal terms (B(s)) cancels out!

This is the crux of MCMC, because it allows us to never calculate the marginal term

The end result is a value between 0 and 1 that is proportional to the ratio of the likelihoods between Psi and Psi star

Generate a random number uniformly between 0 and 1

If that value is less than the ratio R, we accept the new proposal

Takeaway: we always take a step up, we often take small steps down, we rarely (but sometimes) take big steps down

Let's catch our breath for a minute

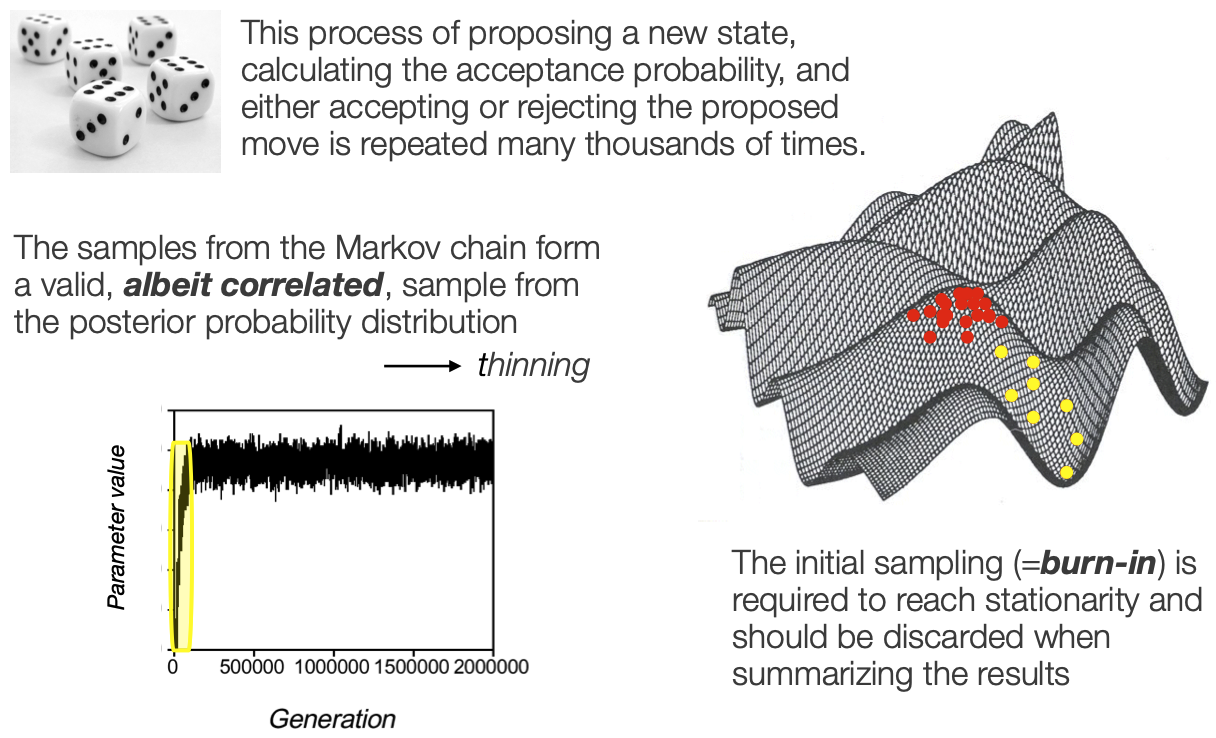

This process is repeated many many many times

All the samples that we keep describe the posterior distribution

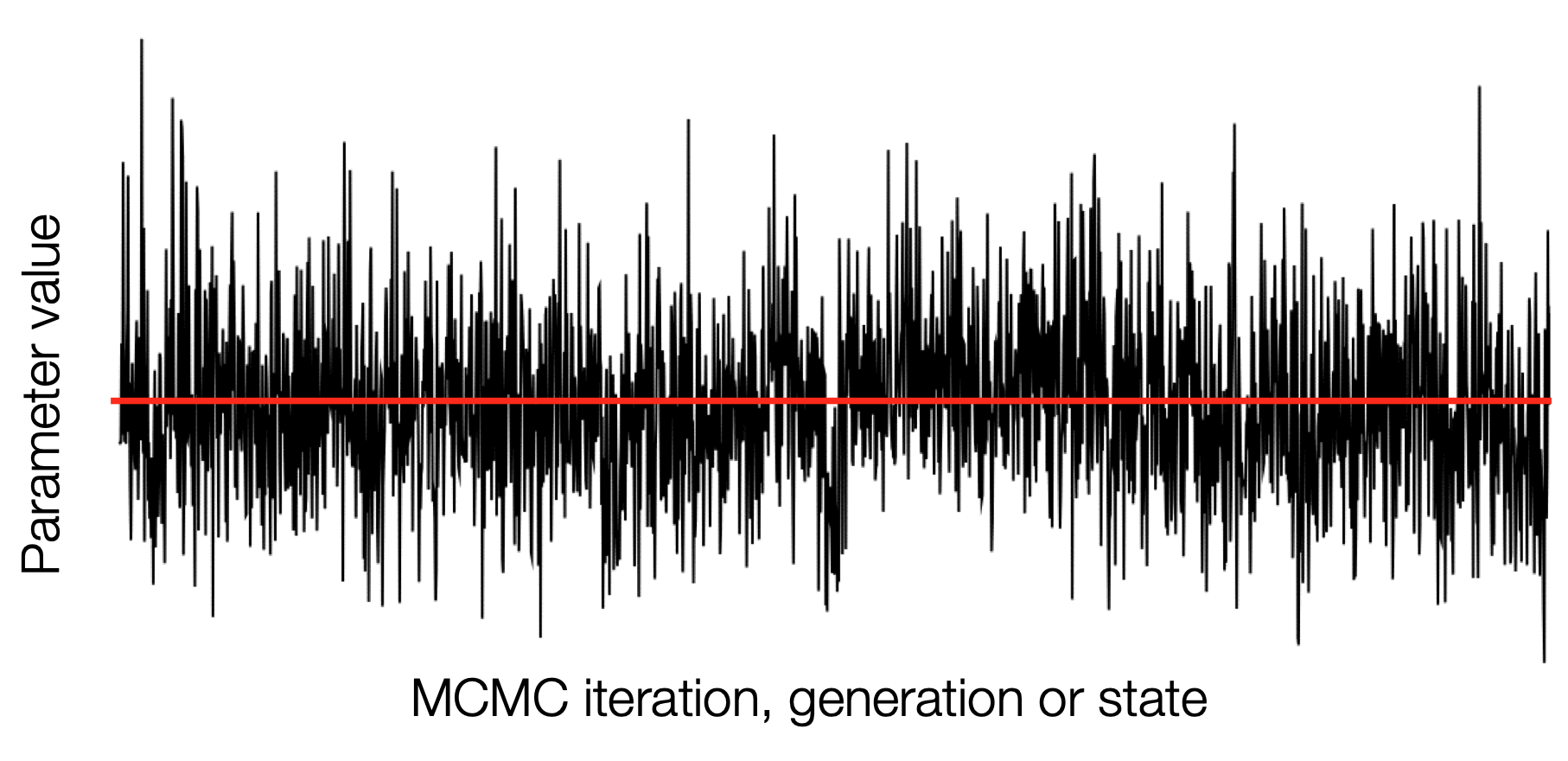

EXPLAIN the trace plot

apologize for no Tom and Jerry

ORIENT WITH THE INTERFACE

RandomWalkMH

normal

autoplay off

autoplay delay 500

animate proposal

walk through how it works for a few steps, then animate, then speed up

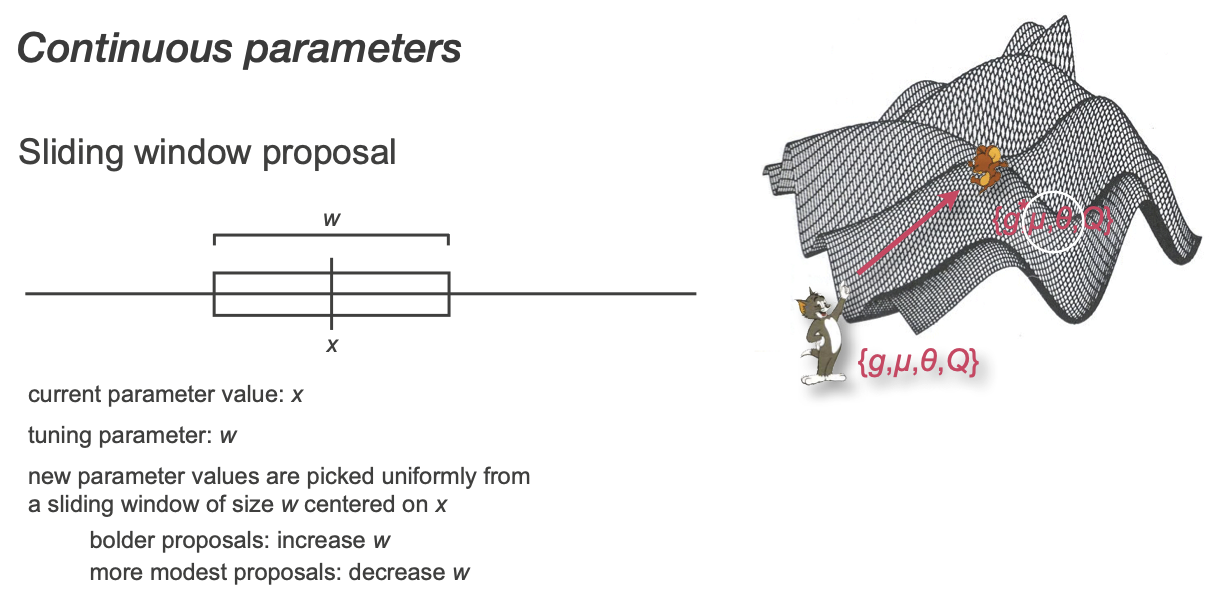

Now we can talk about how the new states get proposed. Many names, a couple major categories.

Operators

Many ways to make new continuous proposals

Simplest example: uniform pick from a window

Tuning prameters are useful!

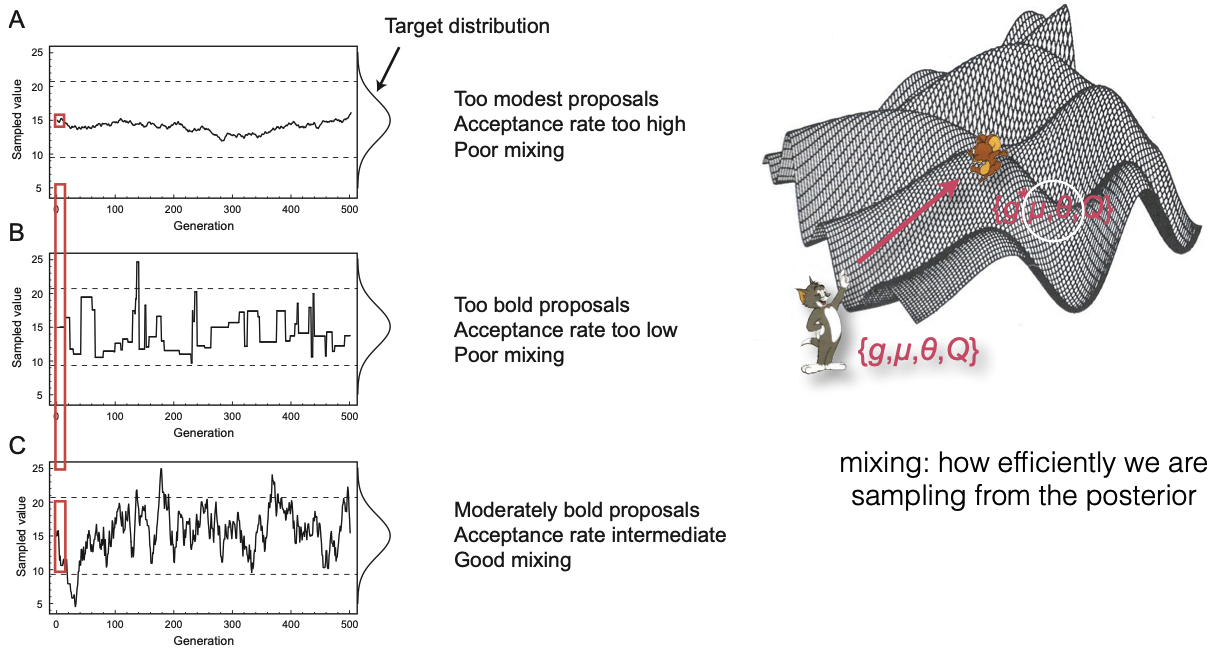

Tuning and mixing

We use the word "mixing" to describe how efficiently we are sampling from the posterior

We can look at the acceptance rate for the operator to see if our proposals are good

mess with sigma on multimodal

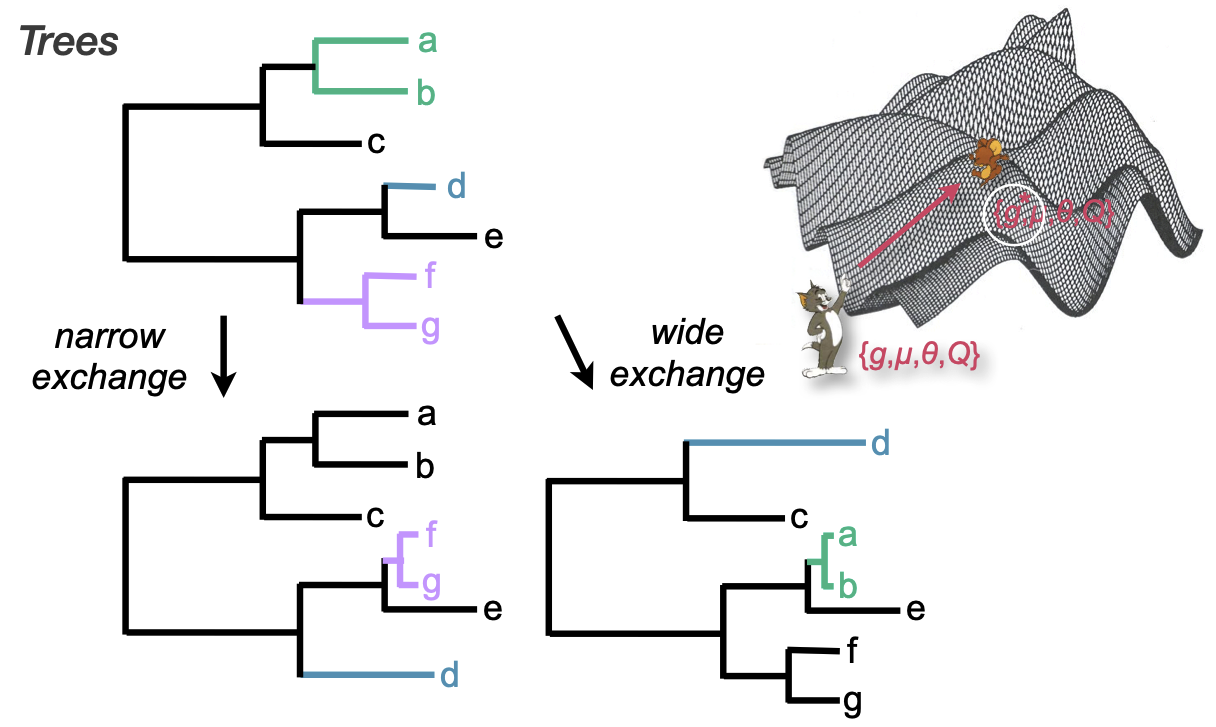

Operators on trees

Narrow moves propose swaps between branches in a local area

Wide moves propose more global swaps

Important! These are the same moves used by ML optimization

MCMC diagnostics, summaries, and interpretation

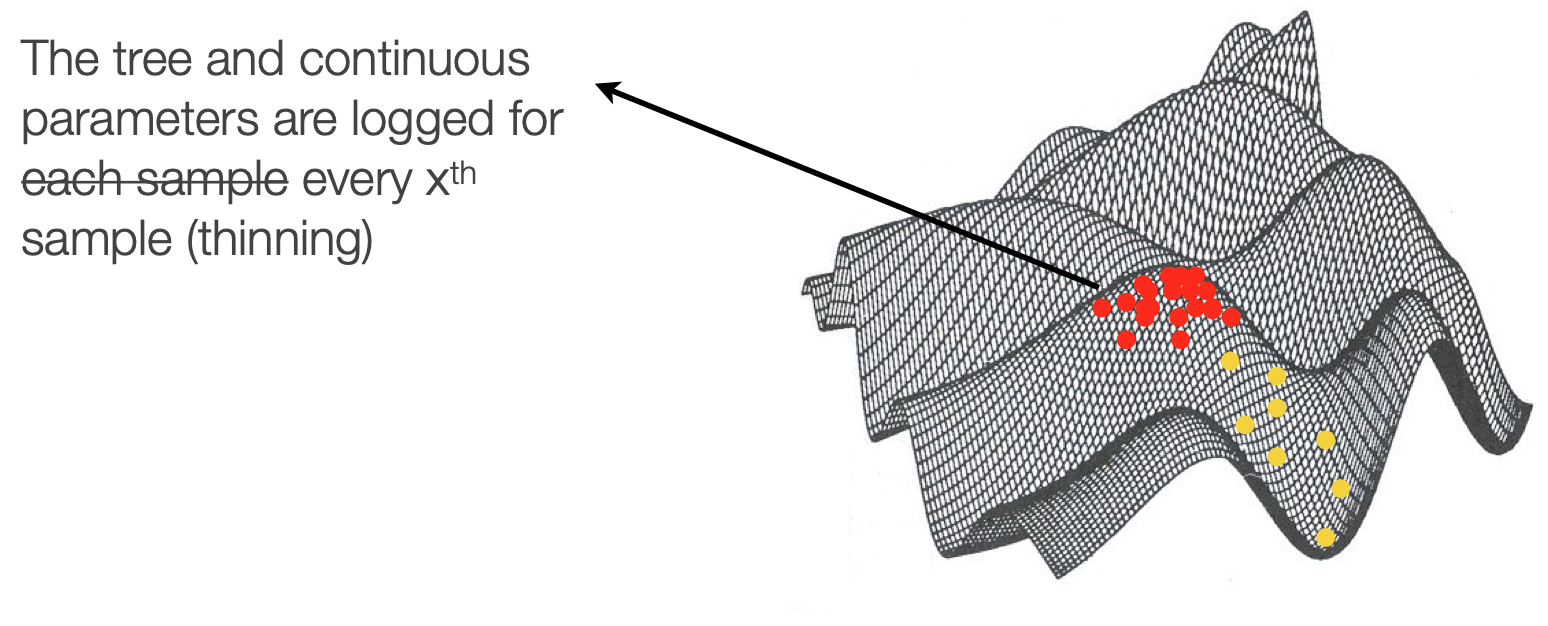

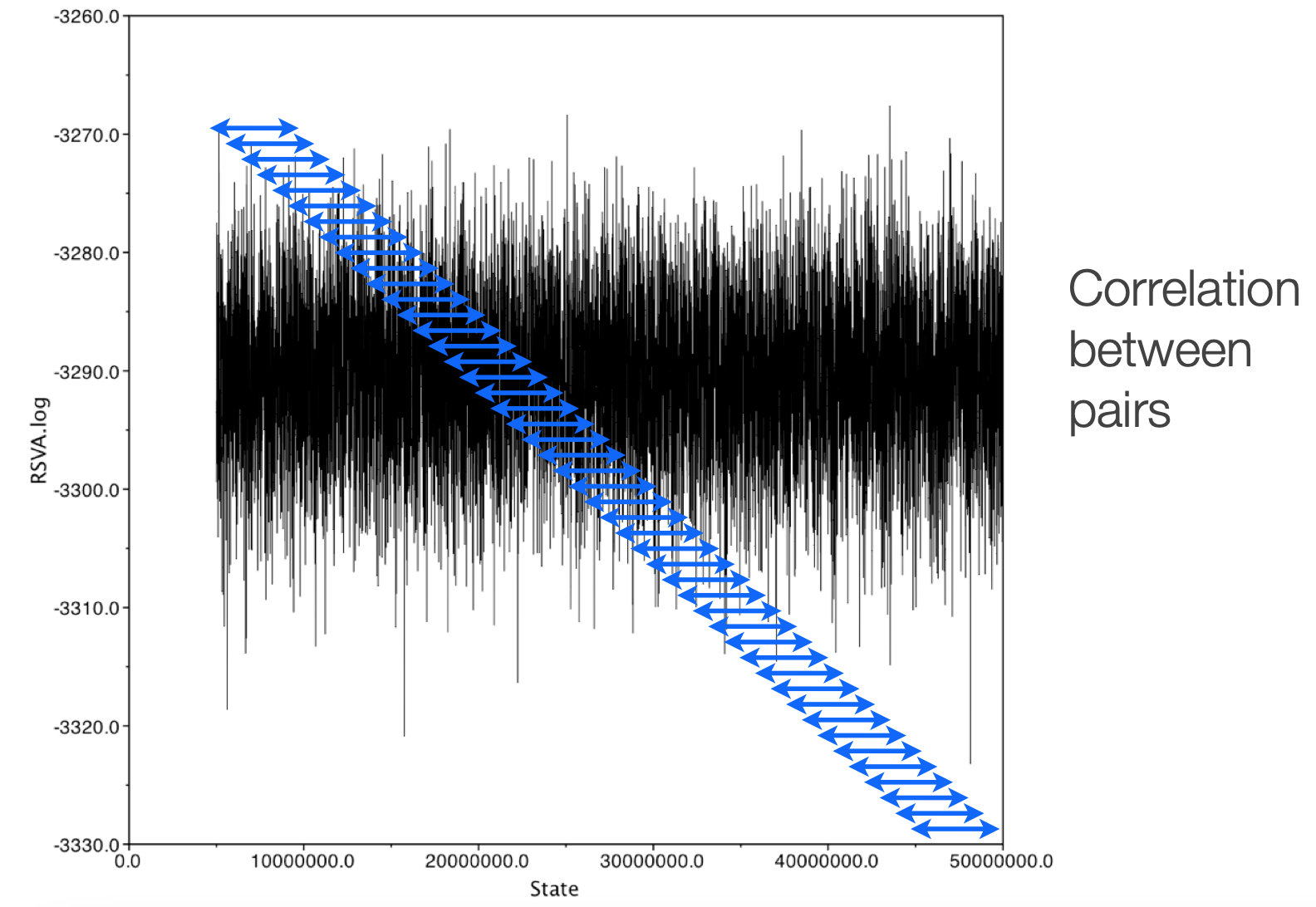

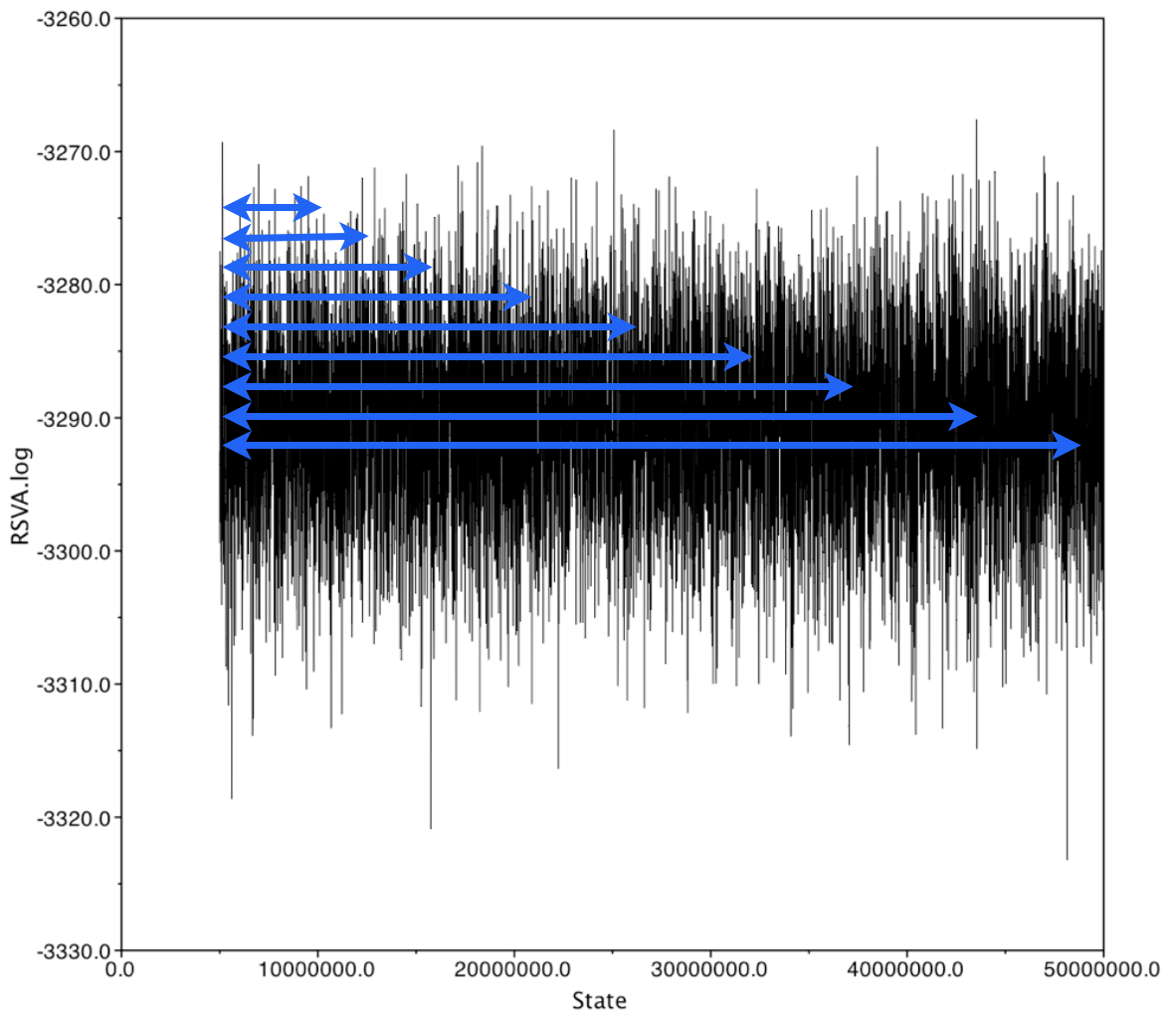

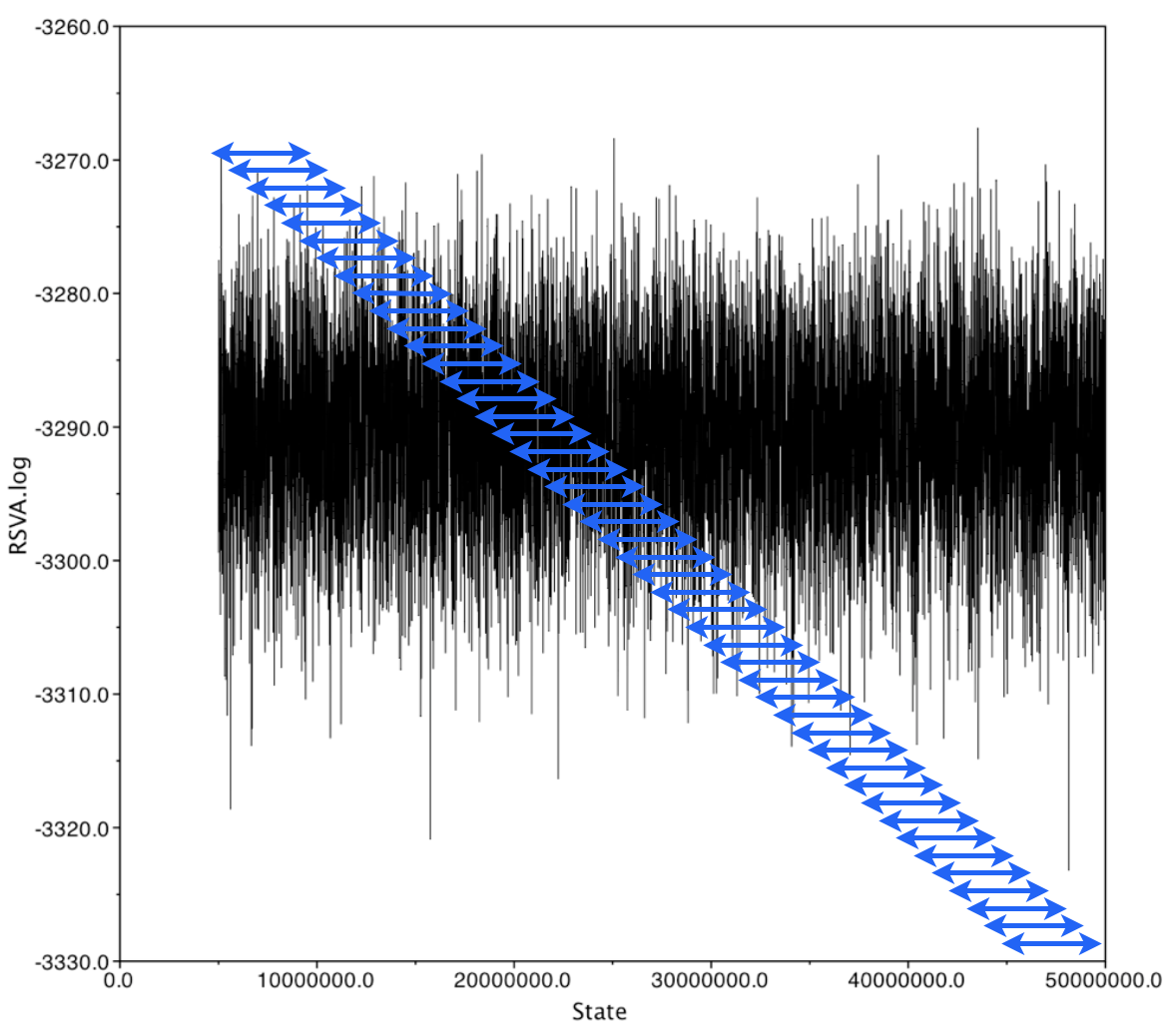

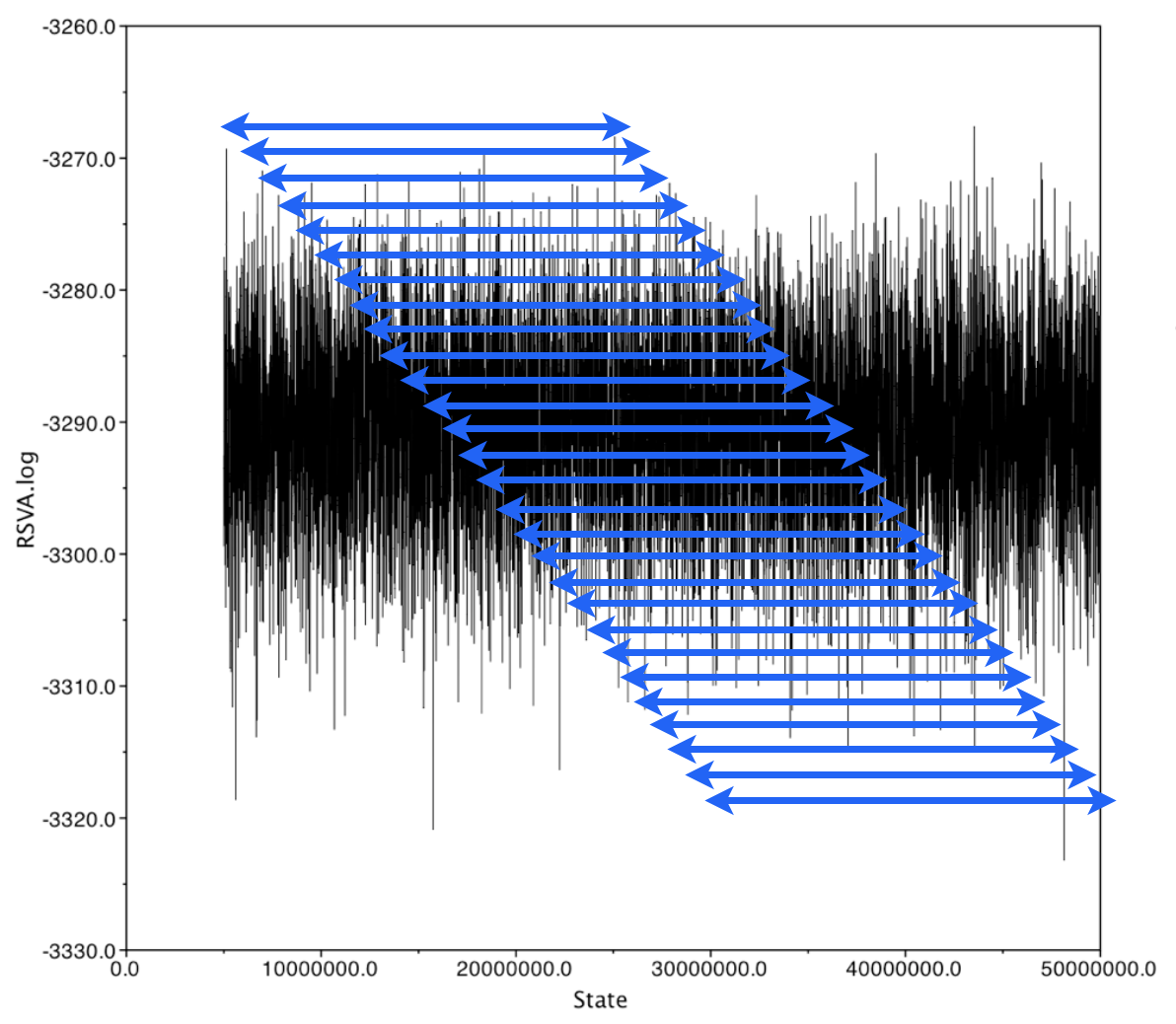

Downsampling

We downsample chains both because of the correlation between states and because of data storage practicality

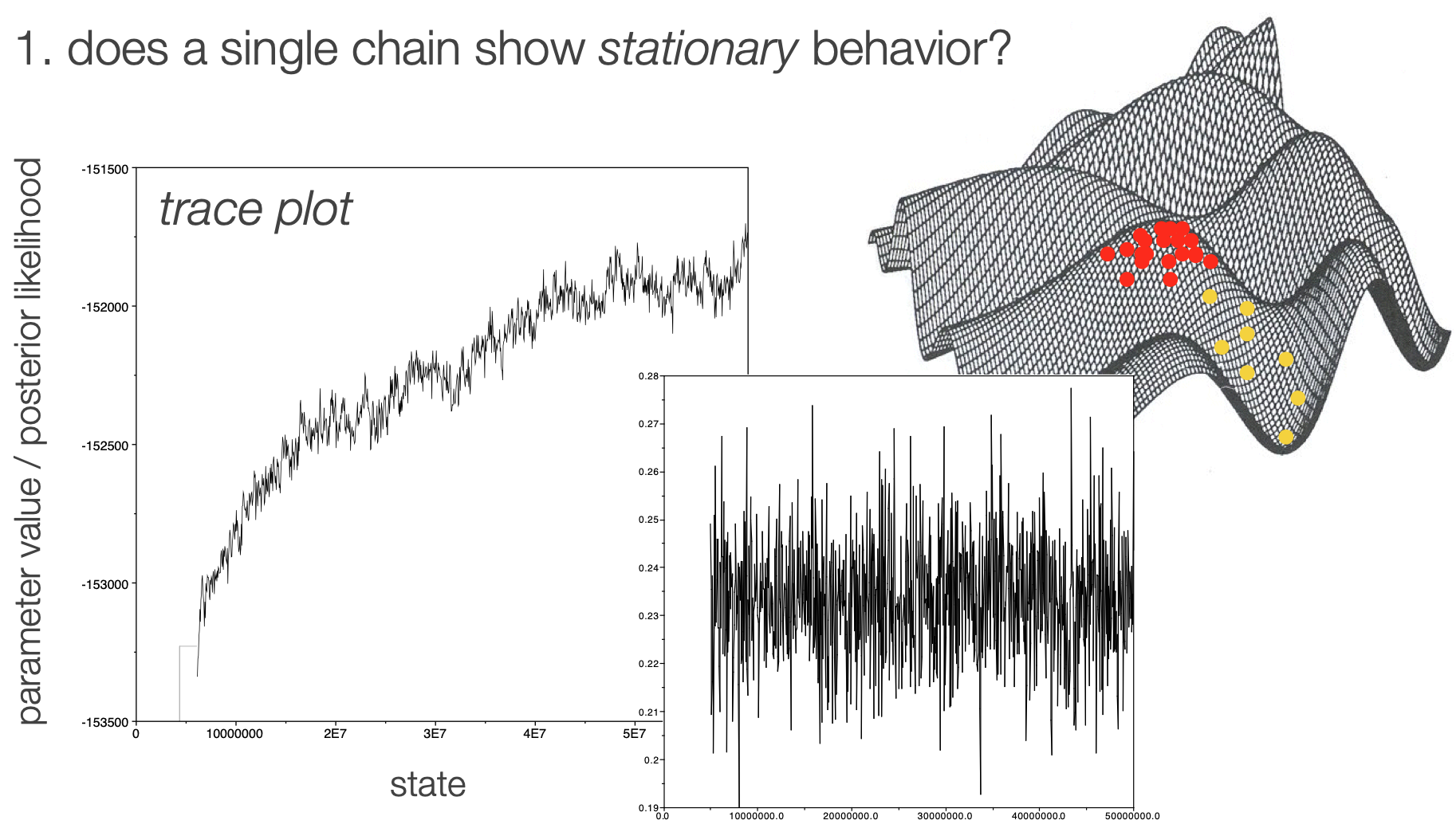

Stationarity

Burn in vs fuzzy caterpillar

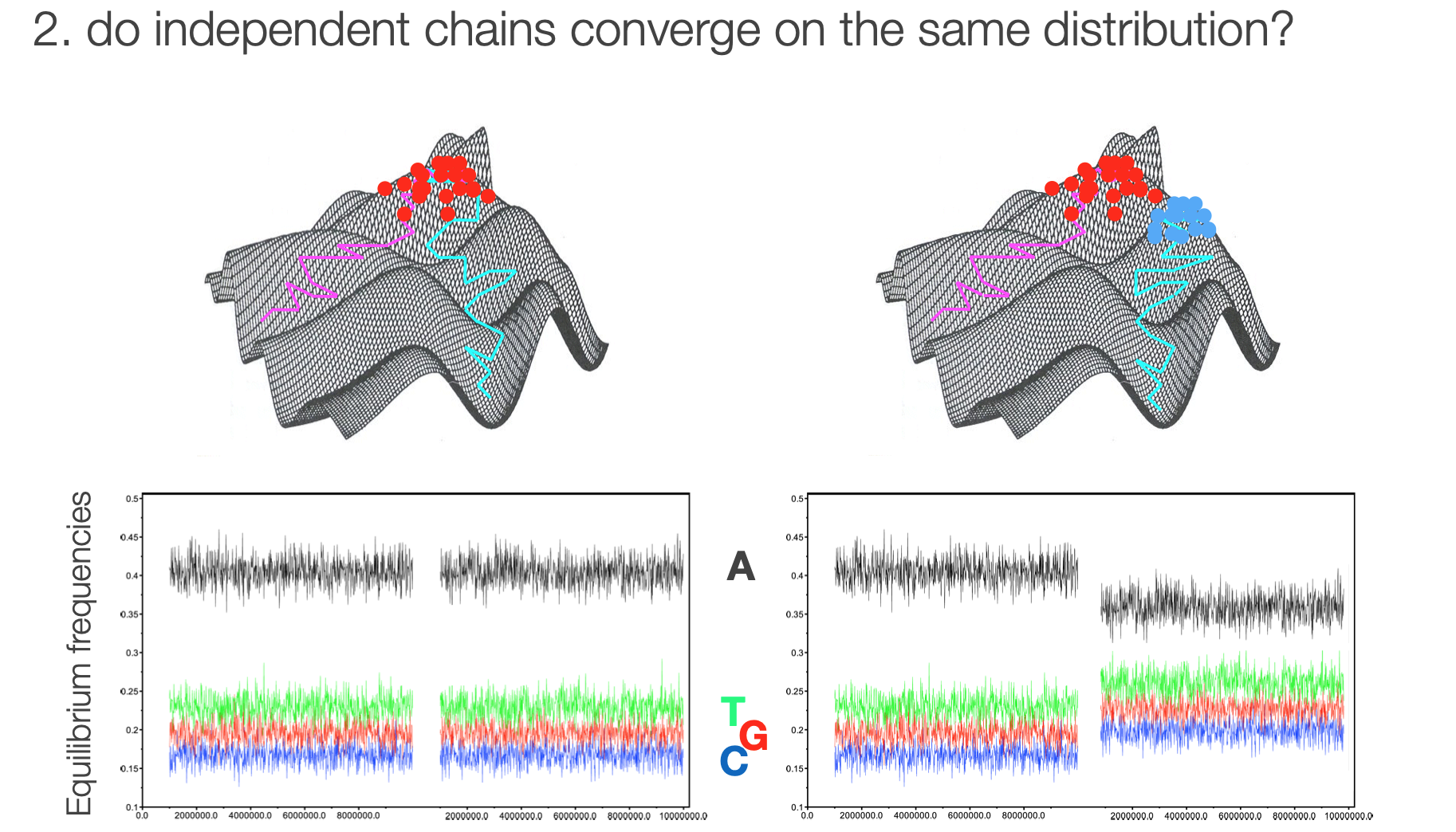

Multiple chains help us determine if we've reached a local or global optimum

Convergence in multiple chains

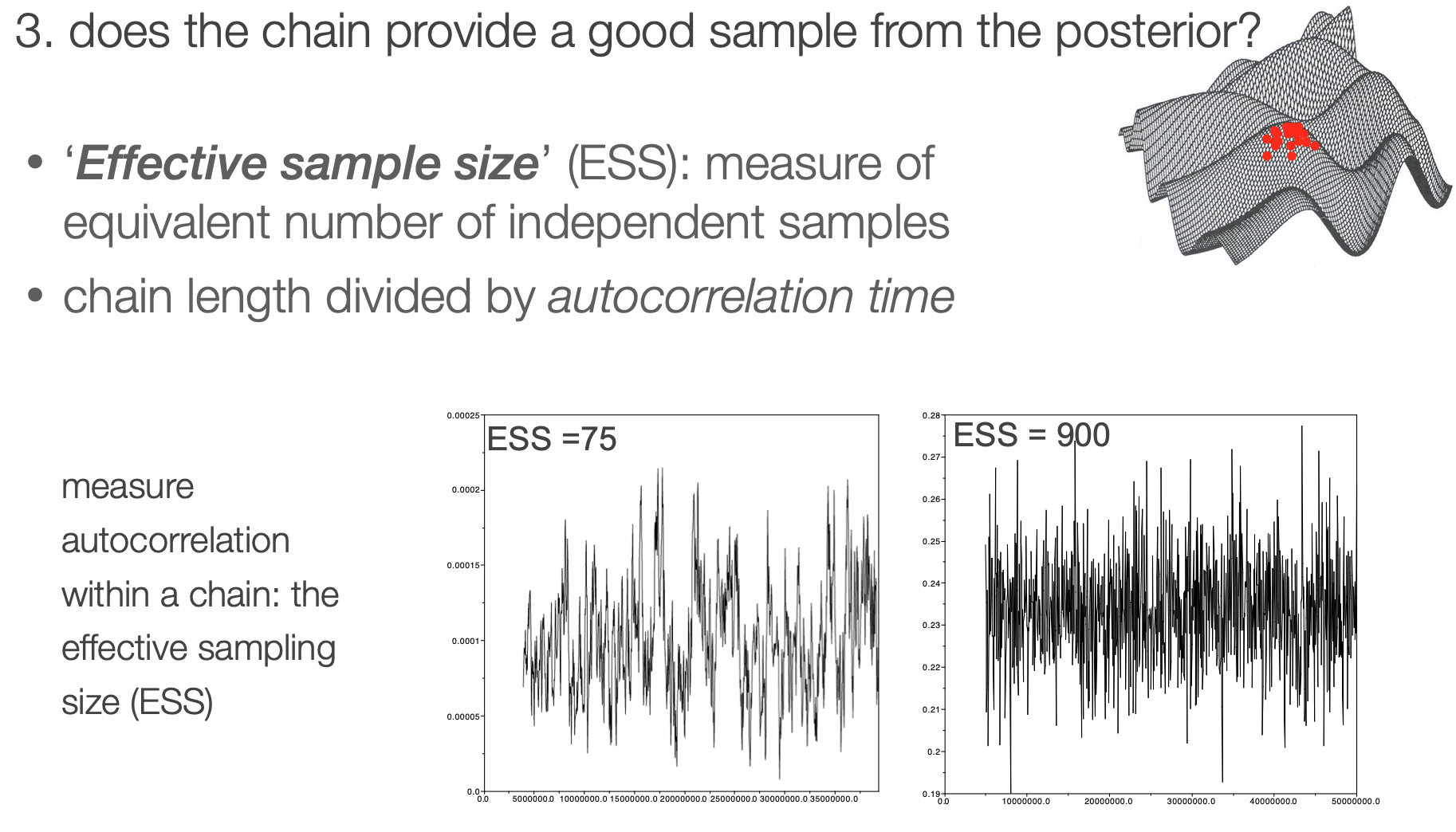

Effective sample size

It is helpful to have an objective statistic for measuring how well the chain represents the posterior

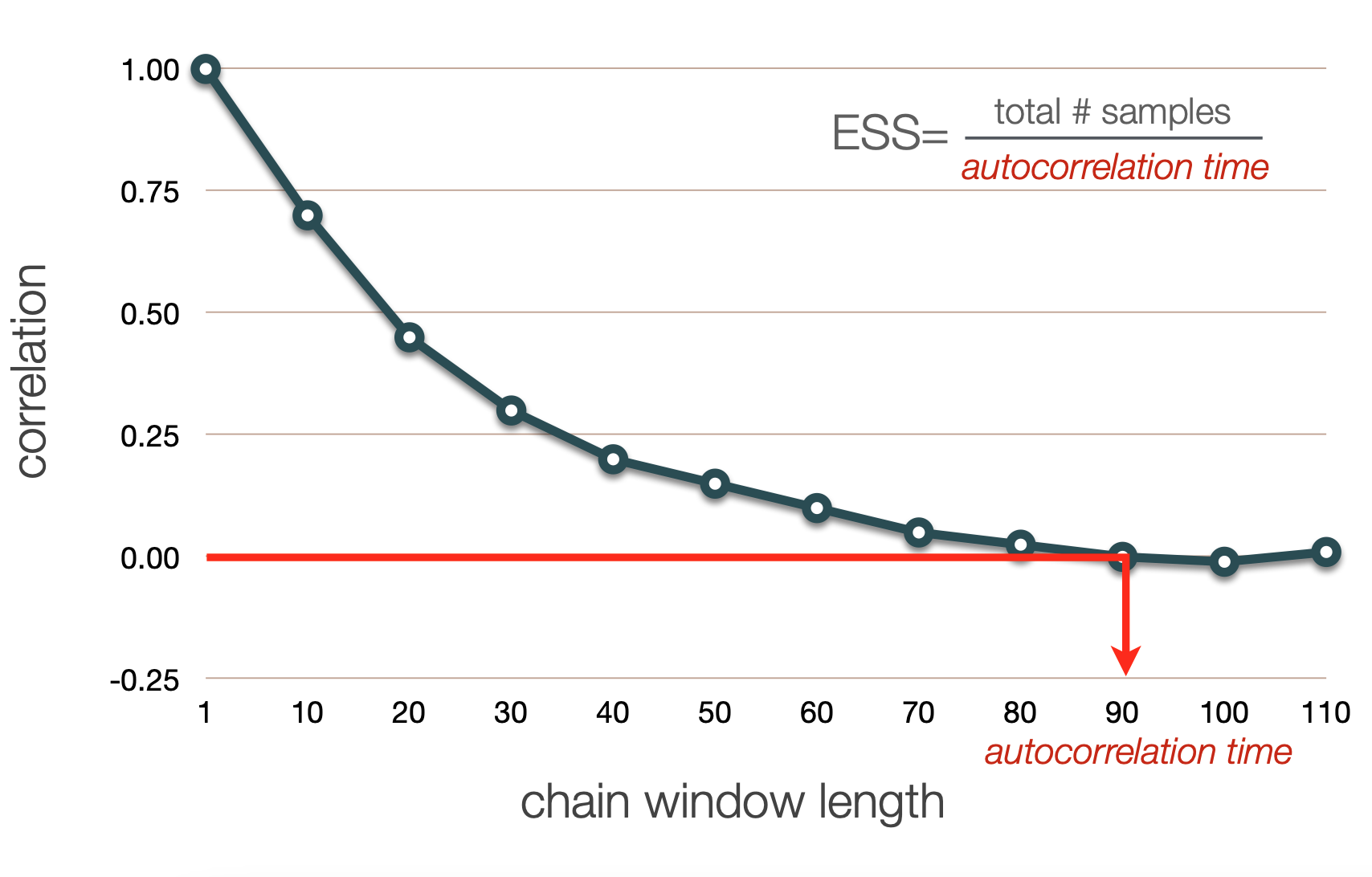

Autocorrelation within a chain

Autocorrelation in a chain is calculated using a "sliding window" approach, where values of the chain are compared across a window of a fixed length. This gets repeated across the whole chain.

Autocorrelation in the chain can be measured using windows of varying widths

ESS Calculation

Recall: we thin chains because two adjacent samples are extremely correlated

In general, we expect an inverse correlation between chain window lengh and degree of correlation

We can define the chain window length for which the autocorrelation drops below a given threshold as the "autocorrelation time"

ESS is calculated as total/a.c.t.

How do we summarize and interpret the results of our Bayesian phylogenetic analysis?

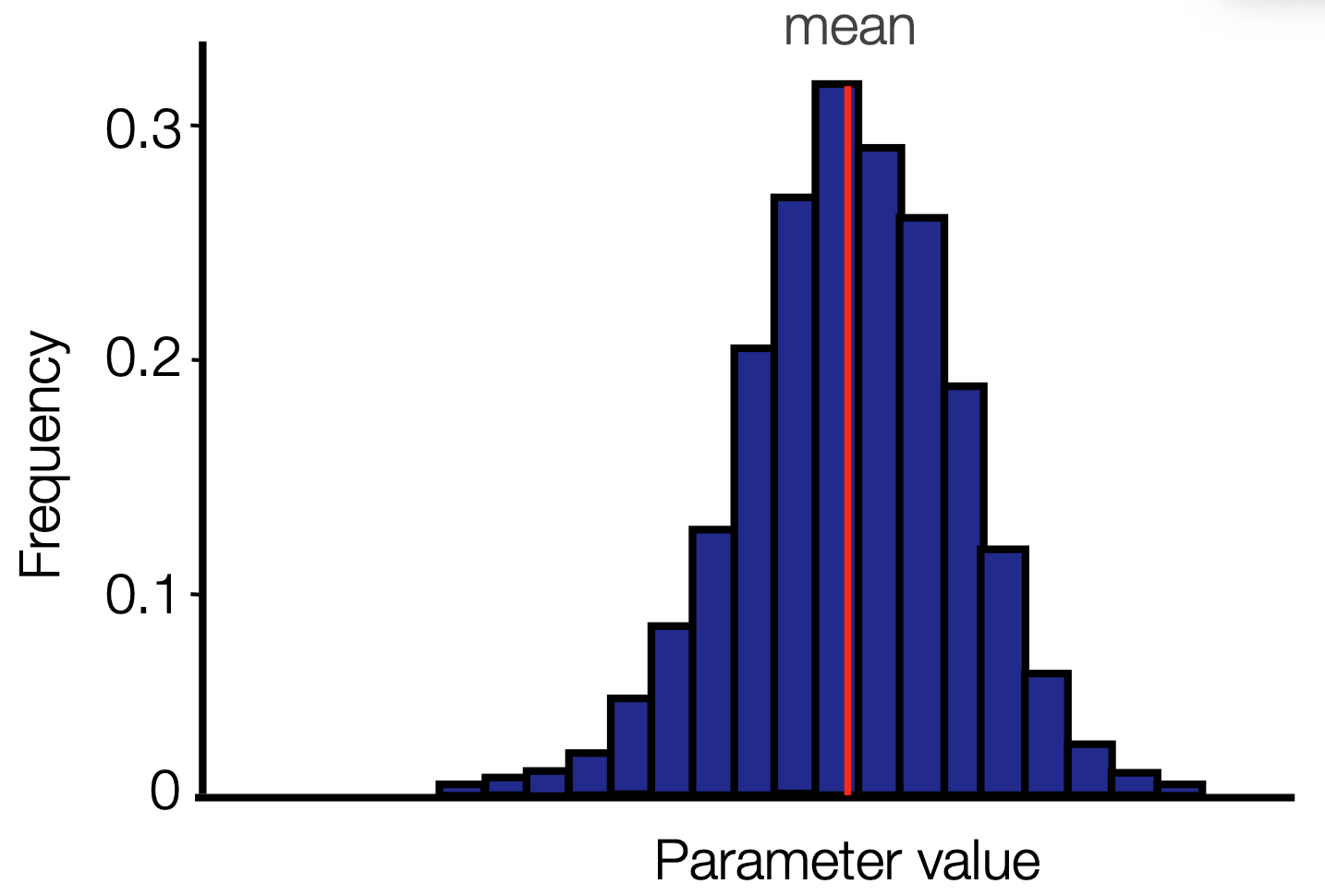

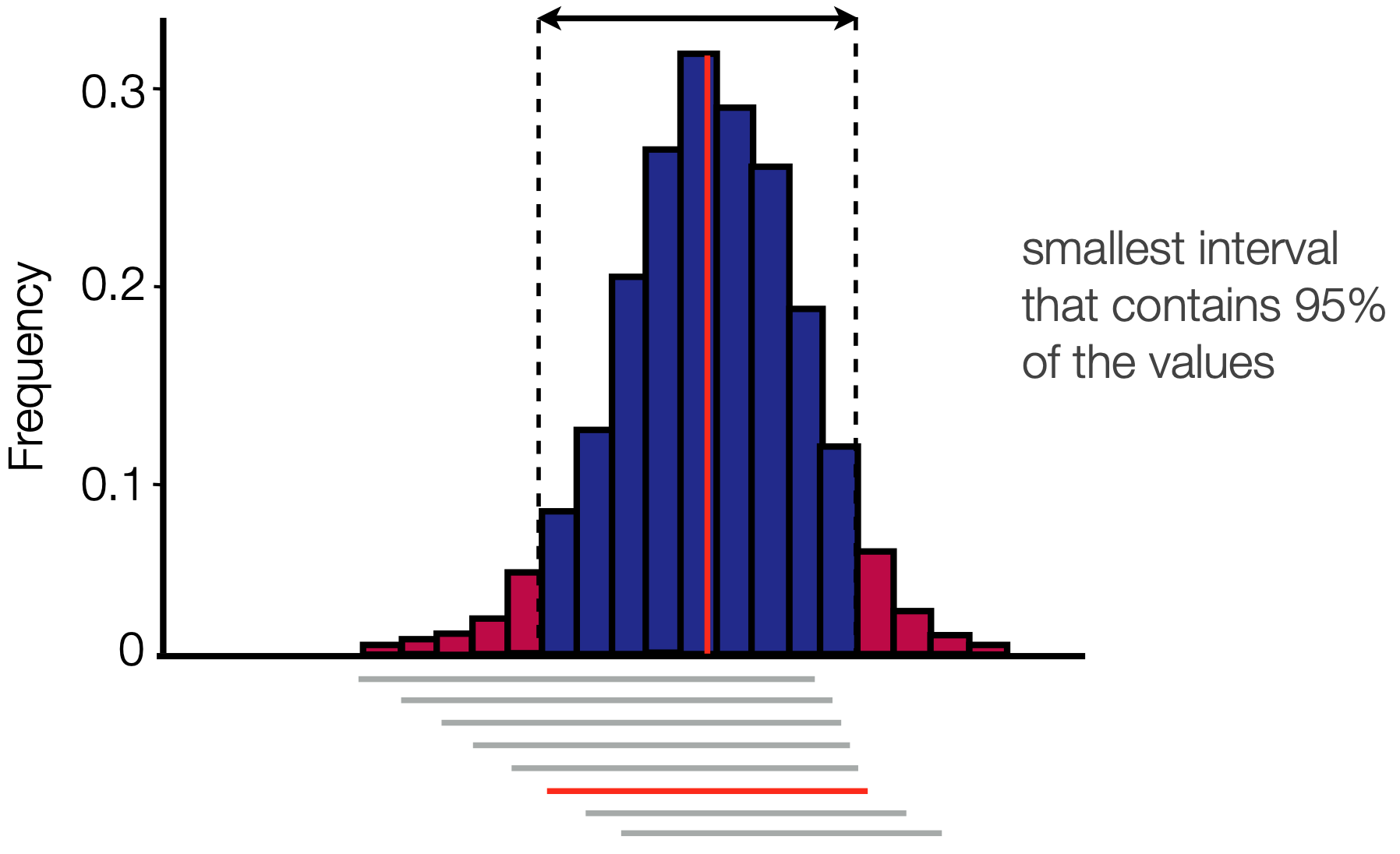

Summary of continuous parameters

For a well mixed chain we see that most of the samples (shown by density) lie closer to the mean and fewer are further away

We can imagine looking at this chain sideways and "collapsing" it

Posterior distribution

When we do this, we get a posterior probability distribution for the parameter. The mean will often be close to the MLE estimate, but we also get a full distribution

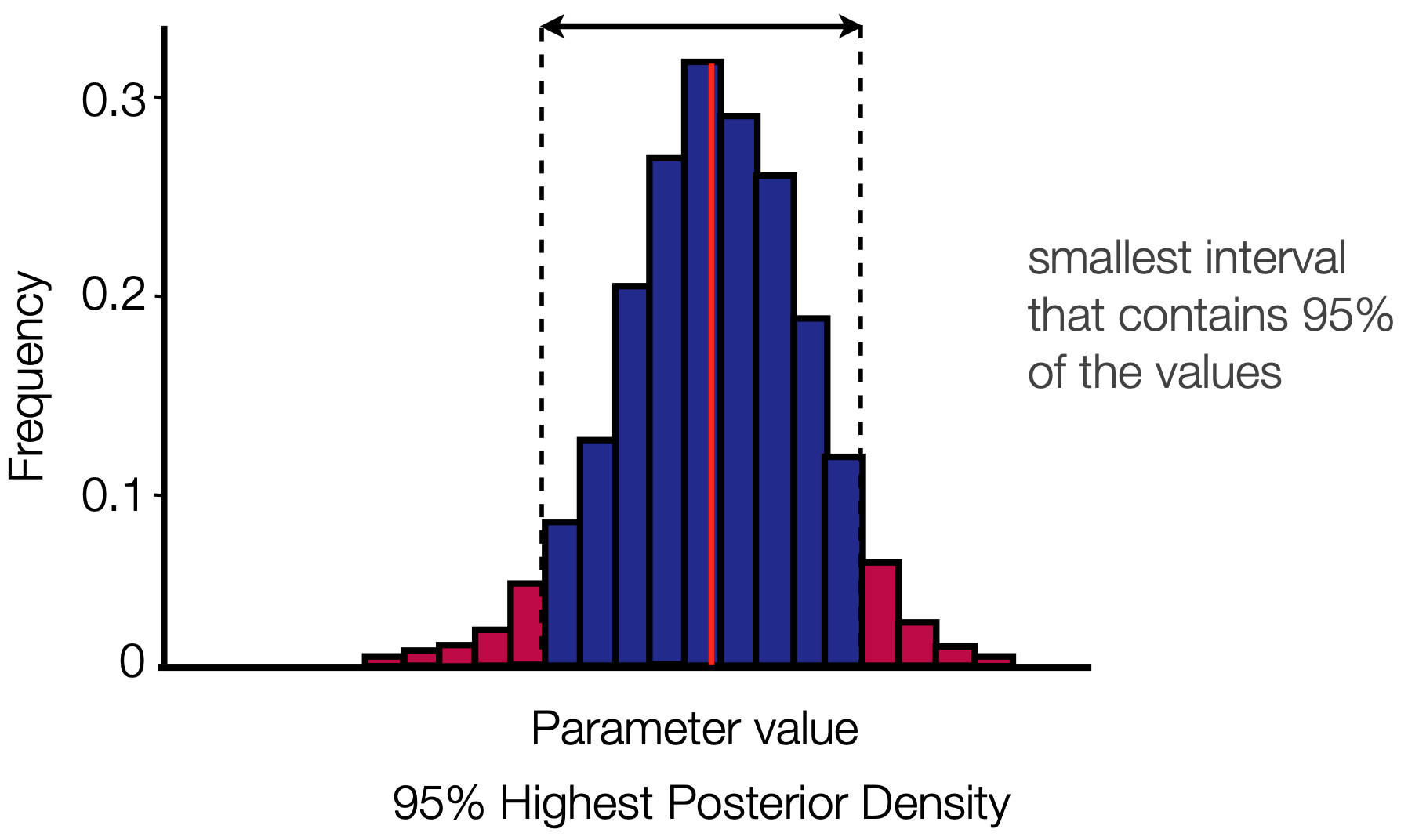

Credible intervals

We usually report not only the parameter mean, but also the 95% HPD

Credible intervals

This is once again calculated using a sliding window approach

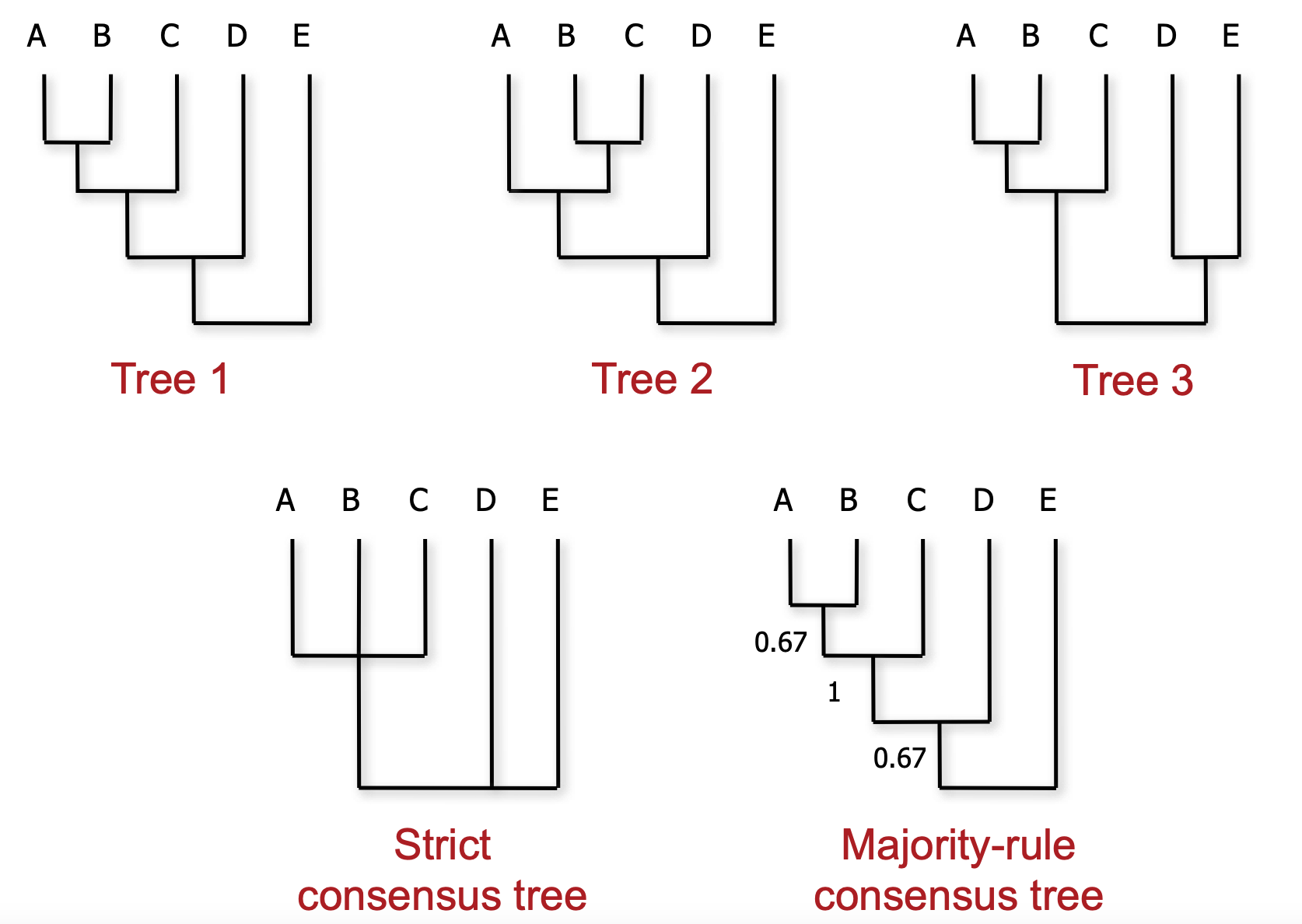

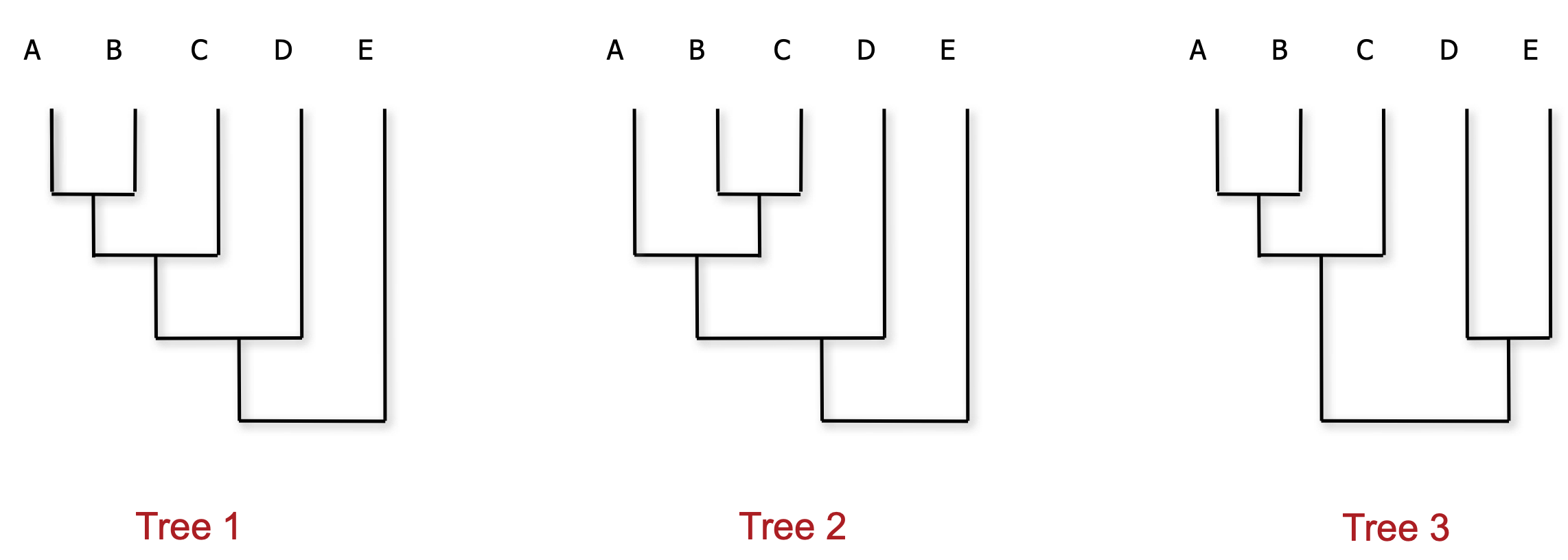

We've discussed how to summarize continuous parameters, however we also want a way to summarize a posterior distribusion of many discrete trees.

How do we choose a consensus?

There are many ways of generating a consensus tree from a sample, with each having its own pros and cons.

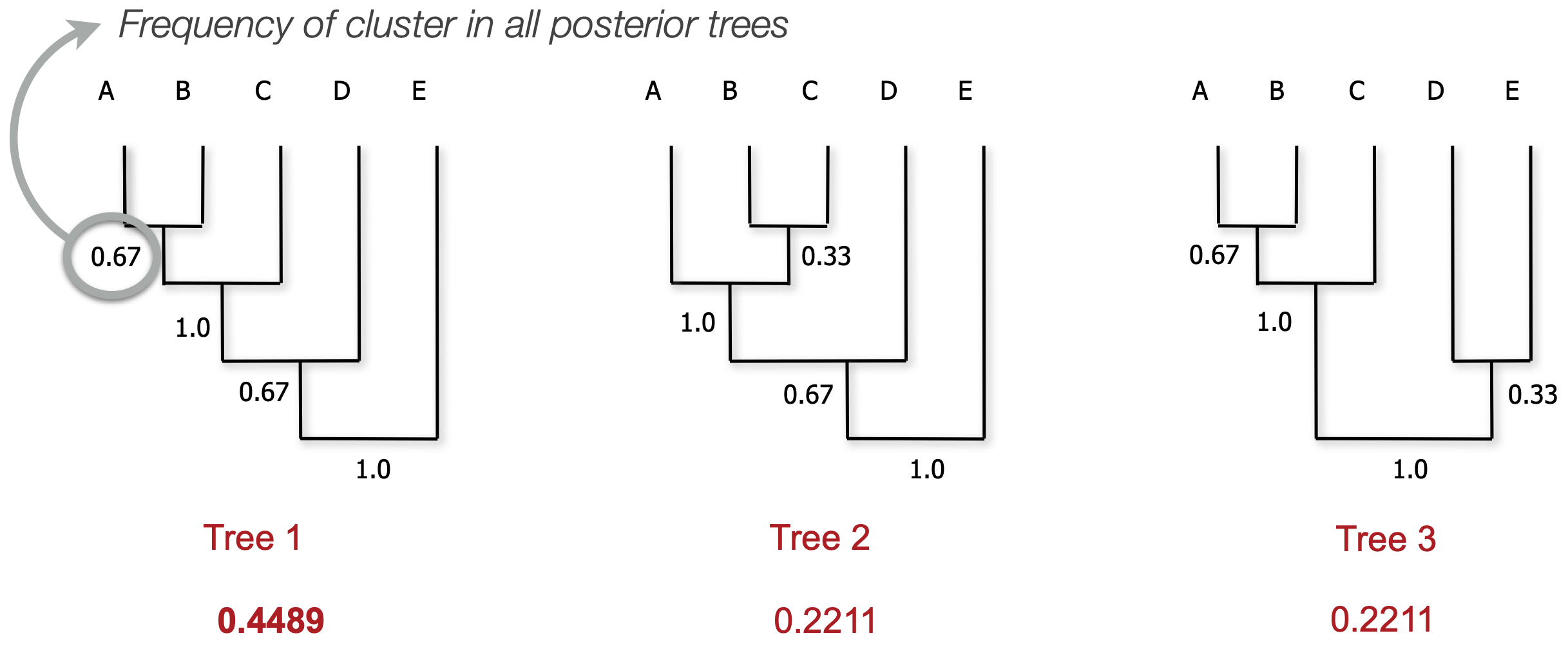

Maximum clade credibility (MCC) trees

We frequently use MCC trees to represent a posterior distribution

MCC tree is a tree from the posterior that best represents the posterior (kind of like a mean)

MCC calculation

We consider each clade (monophyletic subtree) that we observe

Calculate the proportion of posterior trees that clade appears in

We then take the product of all clade frequencies for all trees

The tree with the highest score is the MCC tree

My chain won't converge and I am confused and angry and a little bit scared. What can I do?

In the course of running Bayesian phylogenetic analyses we are frequently frustrated by slow convergence and poor mixing.

Some things might help:

Wait; run more parallel chains (different seeds)

Retune parameters (target $10 \text{--} 70\%$ acceptance)

Propose changes to "difficult" parameters more often (operator weights)

Use different operators

Simplify or make the model more realistic (stronger priors)

For this class we will focus on the first, but in research phylogenetics we have many tools in our toolbelt